BOOKS

The Infectious Pestilence Did Reign

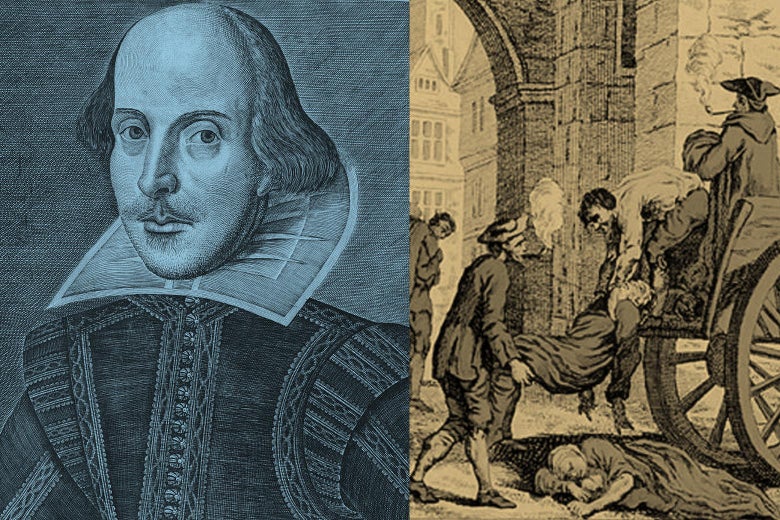

How the plague ravaged William Shakespeare’s world and inspired his work, from Romeo and Juliet to Macbeth.

The Bard survived the plague, referenced it in some of his most famous plays, and took advantage of it.

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University/Martin Droeshout/Wikipedia and Theloveforhistory.com.

This piece is an adapted excerpt from the book The Hot Hand: The Mystery and Science of Streaks by Ben Cohen. Copyright © 2020 by Ben Cohen. From Custom House, a line of books from William Morrow/HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.

One summer day in 1564, a weaver’s apprentice died in a small village in the English countryside, a local tragedy that was immortalized in the margins of the town’s records. Next to the name of the weaver’s apprentice were three ominous words: “Hic incipit pestis.”

Here begins the plague.

The plague wiped out a sizable portion of this particular town. Who lived and who died was seemingly a matter of chance. The plague could decimate one family and spare the family next door. In one house on a road called Henley Street, for example, was a young couple who had already lost two children to previous waves of the plague, and their newborn son was 3 months old when they locked their doors and sealed their windows to keep the plague from invading their home again. They knew from their unfortunate experience that infants were especially vulnerable to this morbid disease. They understood better than perhaps anyone on Henley Street that it would be a miracle if he survived. It was as if every family was flipping a coin unfairly weighted toward heads and betting a child’s life on tails. But when the plague was done with this small village in the English countryside, a little town called Stratford-upon-Avon, the couple breathed a sigh of relief that their young boy was still alive. His name was William Shakespeare.

There’s a possibility that Shakespeare developed immunity to the plague because of his exposure when he was an infant, but that speculation began only centuries later and only because the plague was a constant nuisance to Shakespeare. “Plague was the single most powerful force shaping his life and those of his contemporaries,” wrote Jonathan Bate, one of his many biographers. The plague was naturally a taboo subject for much of Shakespeare’s writing career. Even when it was the only thing on anybody’s mind, nobody could bring himself to speak about it. Londoners went to the city’s playhouses so they could temporarily escape their dread of the plague. A play about the plague had the appeal of watching a movie about a plane crash while 35,000 feet in the air.

But the plague was also Shakespeare’s secret weapon. He didn’t ignore it. He took advantage of it.

One example of this curious phenomenon is Romeo and Juliet. It’s basically impossible to appreciate the truly bonkers nature of this play when you read it for the first time. So let’s do it now. You probably remember the basics of the plot: Romeo and Juliet are born into rival families; Romeo and Juliet fall in love; Romeo and Juliet die. But do you remember how any of that happens? Maybe not. And did you know the plague is what ultimately drives Romeo and Juliet apart? I bet you didn’t. Maybe you vaguely recall the only explicit mention of plague in the entire play: “A plague o’ both your houses!” Mercutio says on his deathbed. But the plague is actually everywhere in Romeo and Juliet.

There’s another death in Act 3 of Romeo and Juliet: a murder! Romeo has killed Tybalt, the cousin of Juliet, who’s supposed to marry Paris, except she’s really in love with Romeo. This is a problem, because Romeo’s family is the sworn enemy of Juliet’s. It’s also a problem because Romeo is now banished after killing Tybalt. Juliet doesn’t know what to do. When she turns to Friar Laurence, he decides there is one way to end the blood feud: He will marry Romeo and Juliet. He hatches a plan that requires Juliet to drink a potion that will put her to sleep for so long that her family will think she’s dead. At the same time, Friar Laurence will have written a letter explaining the harebrained scheme, and Friar John will have delivered that letter to Romeo in the town of Mantua. Romeo will sneak back and steal Juliet away so they can be married and live happily ever after.

It was a pretty terrible plan that worked out pretty terribly—but not for the reasons you might expect. Juliet drinks the potion. Her family thinks she’s dead. Romeo sneaks back to see her. So far, so good. But the whole thing unravels because of what should have been the most reliable part of this ridiculous plan: Friar John never makes it to Mantua, and Friar Laurence’s letter never makes it to Romeo. What happens next is a series of highly unfortunate events. Romeo thinks Juliet is dead. He kills himself. Juliet wakes up from her fake death and learns that Romeo is dead for real. She kills herself. For never was a story of more woe / Than this of Juliet and her Romeo.

Let’s rewind a few scenes and read how Friar John explains to Friar Laurence why he never reached Mantua. Their conversation reveals how the whole foolish scheme fell apart.

FRIAR LAURENCEWelcome from Mantua. What says Romeo?Or, if his mind be writ, give me his letter.FRIAR JOHNGoing to find a barefoot brother out,One of our order, to associate me,Here in this city visiting the sick,And finding him, the searchers of the town,Suspecting that we both were in a houseWhere the infectious pestilence did reign,Sealed up the doors and would not let us forth.So that my speed to Mantua there was stayed.FRIAR LAURENCEWho bare my letter, then, to Romeo?FRIAR JOHNI could not send it—here it is again—Nor get a messenger to bring it thee,So fearful were they of infection.FRIAR LAURENCEUnhappy fortune!

Where the infectious pestilence did reign, / Sealed up the doors … / So fearful were they of infection.

Why didn’t Friar John deliver Friar Laurence’s letter to Romeo? Because he’s stuck in quarantine. Romeo and Juliet are star-crossed once they’re indirectly plague-stricken. The plague is the plot twist that turns the most famous love story ever told into a tragedy.

This exchange is over before most kids reading in high school realize what happened. And yet the whole play turns on this one scene. You might be wondering how the plague could be pulling the strings of Romeo and Juliet, and you might not have known until this very moment. As it turns out, that was the point. Shakespeare was being purposefully obtuse. He wrote in veiled language because the subtext would have been obvious back then. He didn’t have to belabor the point. Mentioning the plague was the Shakespearean equivalent of ending a tweet with “Sad!” There was no need for any sort of further explanation. “It was omnipresent,” says Columbia University professor James Shapiro. “Everybody at the time would have known exactly what those one or two lines meant.”

But this subtle reference in Romeo and Juliet was nothing compared to how Shakespeare would use the plague later in his life.

From the beginning of 1605 to the end of 1606, scholars believe, Shakespeare wrote King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra. The scholar J. Leeds Barroll once called it “a concentrated efflorescence of creative power as strong or stronger than any other in Shakespeare’s career".

The rule of thumb until not too long ago was that Shakespeare wrote two plays every year, but that was because literary scholars are not exactly statisticians. They came to that number simply by dividing the number of plays he wrote by the number of years in which he wrote them. According to their calculations, if Shakespeare wrote 10 plays in five years, he wrote two plays a year. But there was a rub. And the rub is that it wasn’t remotely true.

“It turns out Shakespeare always tended to write in inspired bunches,” Shapiro says. “It’s something that took me a while to wrap my head around simply because I always kind of believed the unsubstantiated claims that he was churning out two plays a year. But that’s never what he did.” Shakespeare ran hot and cold. His plays were not spread over the course of his career. They were clustered. “Once you start seeing those plays are really bunched, you start asking: Well, what accounts for a lot of plays in a very short period of time?” Shapiro says.

It was the oddest bit of circumstance in this case: a plague year. The plague closed London’s playhouses and forced Shakespeare’s acting company, the King’s Men, to get creative about performances. As they traveled the English countryside, stopping in rural towns that had not been stricken by the plague, Shakespeare felt that writing was a better use of his time. “This meant that his days were free, for the first time since the early 1590s, to collaborate with other playwrights,” Shapiro wrote in his book The Year of Lear: Shakespeare in 1606, the best account of this strange time in his life.

Shakespeare also benefited from the plague because the plague killed off his competition. The King’s Men would eventually take back their indoor theater spaces because of this disease that preyed on the young. The plague created the circumstance that enhanced Shakespeare’s talent. It was right around this time when he caught fire, and King Lear, Macbeth, and Antony and Cleopatra rushed out of him.

“Three really extraordinary tragedies,” Shapiro says. “I’m always interested in how and why this mysterious thing happens of understanding fully the world that you are in and being able to speak to it and for it.” It’s often tempting for the scholars to scrutinize certain moments of Shakespeare’s career through the lens of his personal life. The issue with that line of research is that they still don’t know all that much about it. “We have no idea what he was feeling,” Shapiro wrote in his book. “We know a great deal more about how a rodent-borne visitation in 1606 altered the contours of Shakespeare’s professional life, transformed and reinvigorated his playing company, hurt the competition, changed the composition of the audiences for whom he would write (and in turn the kinds of plays he could write), and enabled him to collaborate with talented musicians and playwrights.”

Shakespeare was not a metronomic writer. He was streaky. He wrote in runs. And this run was dependent on forces beyond his control. It was because of the plague that he was able to turn a period of great societal upheaval into something else altogether: a resplendent, historic stretch of unexpected literary success.

Listen to author Ben Cohen talk about his book on the episode of Slate’s podcast Hang Up and Listen below, or subscribe to the show on Apple Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, Stitcher, Google Play, or wherever you get your podcasts.

No comments:

Post a Comment